By Owen V. Johnson

Ernie Pyle’s influence appears in the most unexpected places.

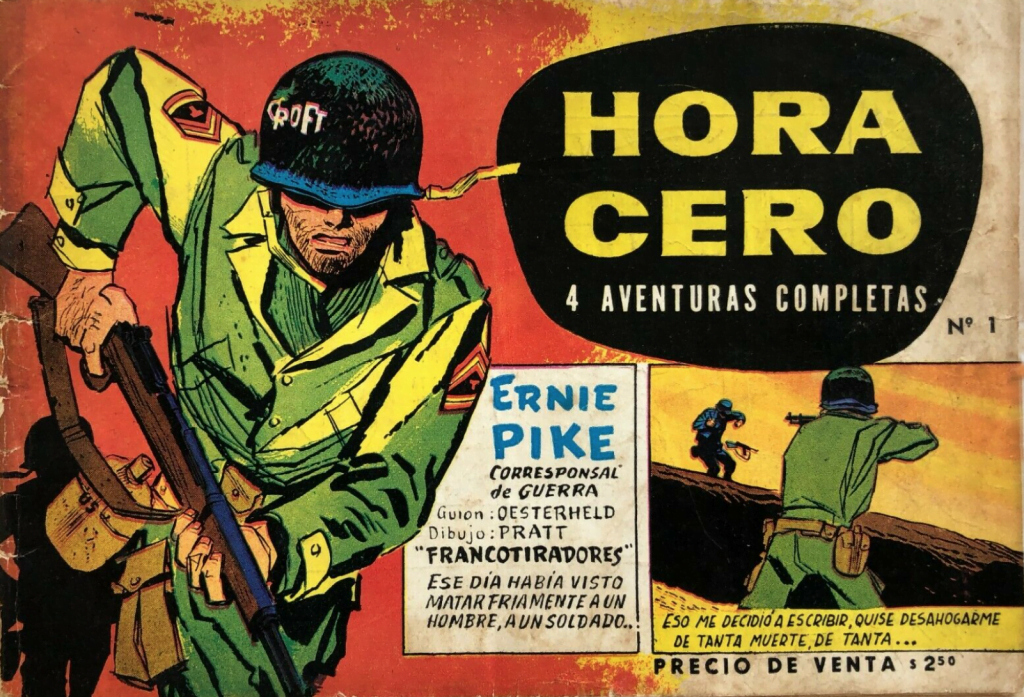

In 1957 Héctor Germán Oesterheld (1919-1977?), an Argentine writer, and Hugo Pratt, an Italian comics artist, created a fictional war correspondent named Ernie Pike as a World War II character in their historietas (comics). The stories were first published in Hora Cera, an Argentine magazine, part of the publishing house Editorial Frontera that Oesterheld established. Pike became part of the Argentine popular imagination. Oesterheld was responsible for much of the success of Frontera by his excellent writing and the interesting adventure stories he spun.

Oesterheld assembled a topflight team of artists including the Italian Pratt, who illustrated the first Ernie Pike stories. Pratt, related to the actor Boris Karloff, was the son of an Italian soldier who was captured in North Africa and died in 1942 as a prisoner of war. His son and wife were also interned in a prison camp for a time. After the war young Pratt organized entertainment for Allied troops in Venice, where he had grown up. He was responsible for the first sketches of the person of Ernie Pike. His model was Oesterheld, although that was not what Oesterheld planned. Pratt returned to Europe in the early 1960s, where he published the Ernie Pike stories under his own name. He died in 1995. A succession of illustrators took over the Ernie Pike stories back in Argentina.

Pike makes handwritten entries in his notebook (something Pyle didn’t do), including both a general assessment of the situation, as well as personal impressions from the position of a civilian observer who knows war. As Pyle was in his writings, Pike is mostly an observer, but he differs from Pyle in that he is clearly a pacifist, something Oesterheld’s readers came to expect. He focuses on tragic events where things have gone wrong. Far more important for Oesterheld was the concept of the collective hero, in this case, the soldiers about which Pike was writing.

Initially Oesterheld placed Pike in World War II. Those stories place Pike in North Africa, the European Theatre and the Pacific, all places that Pyle wrote about, but Pike also can be found in the steppes of Russia. There are no descriptions of battles, only personal stories. As international communication specialist John Lent wrote, “All of [the characters] shared real, believable feelings and emotions, and a deep dislike for the situation they were stuck in.” Oesterheld, at the time a humanist, did not make judgments about the countries that were fighting, but only about personal morality. There is no clear good and evil. Germans were the good guys just as often as American G.I.s. In this regard, we should remember that even Ernie Pyle empathized with ordinary German soldiers captured in the final stages of the North African fighting in 1943.

Oesterheld, influenced by Stephen Crane, Erich Maria Remarque and Leo Tolstoy, among others, grew increasingly anti-war. He had Pike tell stories about the Korean War and the Vietnam War. Pike was an active character in these new stories and critical of US participation in Vietnam. Oesterheld was slowly becoming a political radical. He eventually affiliated with Montoneros, a left-wing terrorist group. He even wrote a strip about the Cuban guerilla fighter Ché Guevara.

Oesterheld was captured, imprisoned and tortured by the Argentine government in 1977 and apparently killed no later than early 1978. His family believed he was among the estimated 30,000 people to have disappeared and been killed by the government of the generals. In 1977 Oesterheld’s three daughters and their husbands also disappeared. One grandson, Martín, was born in captivity. Oesterheld’s widow, Elsa Sánchez, learned about the boy and recovered and raised him. A second grandson was raised by his paternal grandparents.

Pike outlived Oesterheld. In the follow-up to the attempted Argentine effort to seize the Falkland Islands from Great Britain in 1982, Pike reappears in a story written by Ricardo Barreiro. On one occasion, Pike asks an Argentine journalist whatever happened to a friend name Héctor Oesterheld, saying that he hadn’t been able to find him in Buenos Aires. The journalist tells him what happened and warns him not to mention Oesterheld’s name in public.

Collections of the Ernie Pike comics have been published not only in Spanish but also in French, Dutch and Italian. None of the Ernie Pike stories have ever been published in English, probably because of Oesterheld’s more complicated approach to war, his later radicalism and Pyle’s reputation as part of the so-called Good War. What Oesterheld succeeded in capturing in Ernie Pike was Ernie Pyle’s description of the pain and tragedy of war and how it changes people, and his ambivalent attitude toward war in general. That’s one of the themes of his writing that has received less attention over the years but that his World War II readers would have recognized.

— Owen Johnson is a historian, associate professor emeritus at Indiana University and author of “At Home with Ernie Pyle.”